By Barbara LaMonica

While going through 18th and 19th century deeds in our archives I noticed that some transactions were noted in “pounds, shillings and pence” years after the colonies won their independence from Britain. Was the United States still using British money, and, if so, why?

Initially, there was a lack of cash in the colonies, as Britain did not allow the colonists to mint their own money, nor would the mother country export any silver or gold coins. Furthermore, the colonies suffered an unfavorable balance of trade since the goods imported from England exceeded the amount of colonial exports. Therefore, the colonies were forced to improvise methods of currency exchange for domestic as well as international transactions.

As independent bodies without a central government or unified money system each of the Thirteen Colonies could establish their own methods of currency and exchange. However, difficulties arose as one colony did not necessarily accept the currency of another colony. For example, in seventeenth century the New England colonies actually used wampum as currency which was often not accepted as payment for goods in the southern colonies, and England rejected Wampum outright as payment for debts. Another method of payment was by barter and commodity currency. Tobacco and corn were accepted as payments but again not across the board. To further confuse the matter, the colonies would convert commodities into money values expressed in British terms- pounds, shillings, pence although there was not actual British currency. But again not every colony would agree. A New York pound may have a different value than a Massachusetts pound or a Pennsylvania pound.

Another method was paper money backed by real estate. A colony would issue paper money to an individual who took out the loan backed by real estate collateral. These paper notes circulated freely in the local economy. During the eighteenth century several colonial governments experimented with “fiat money” which was based on faith in the issuing party. However, Britain tried to outlaw this practice by passing Currency Acts which tried to limit use of the bills only for paying taxes. Additionally, the colonies were forbidden from backing the bills with hard coins. Therefore, British creditors would not accept them.

Due to colonial trade with the West Indies, Spanish coins of gold and silver were the most prevalent currency in the colonies. The value of these coins was denominated in Colonial shillings, and goods in British pounds, again not real British money but only British terms. And once again the value of the currency often fluctuated from colony to colony.

These currency issues which caused the colonies grave economic problems eventually led to the American War of Independence. The Continental Congress then issued their own money, “continentals;” however, many colonies printed too much money causing devaluation. The British further compounded the problem by flooding the colonies with counterfeit continentals. After the American victory states were prohibited from printing their own money, and only the federal government could print and value money.

In spite of establishing the US dollar as the national currency at the end of the war, other currencies still circulated, especially Spanish money which still carried British denominations. This type of currency was most typical in rural areas. It was not until the time of the Civil War that the American dollar finally won over other currencies.

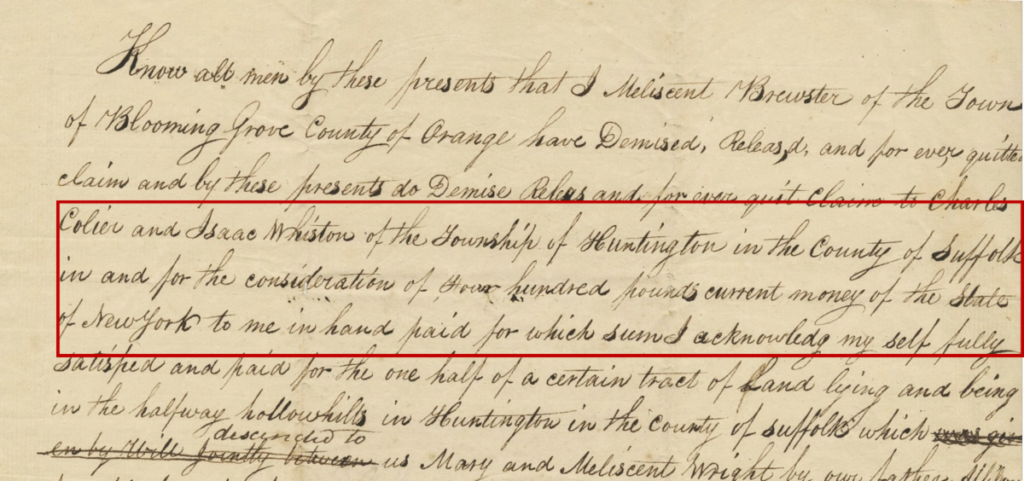

So our deed of 1811, below, succinctly illustrates this point. The reference to pounds is not British money but a still circulating currency labeled in British denominations.