By Jeff Richman

CONKLIN, JR., RICHARD (1756-1818). Seaman, Patriot privateer, United States Navy; associator, Huntington, New York. Much of what we know about Richard Conklin Jr. is thanks to family records, inscriptions on gravestones, and some military records, such as headstone applications for military veterans. Richard was born on January 28, 1756, in the Huntington/Cold Spring Harbor area of Long Island, to Richard Conklin Sr., born in Smithtown in 1726, and Rebecca née Titus, born in 1732. The Conklin family arrived originally from England in the first half of the 17th century, settling in Huntington, according to The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut (1913), by Frederic G. Mather.

Richard Jr. had several siblings, all born in Huntington: Jemima Conklin Mather (1758-1805), Titus Conklin (1761-1855), Charlotte Conklin (1765-1810), Buel Conklin (1770-1822), and Enoch Conklin (1778-1847.)

In 1775, Richard Jr. signed the Association Test (Articles of Association) in protest of the British occupation of New York Province and, sometime afterwards, fled Long Island for refuge in Connecticut. On May 8, 1775, 403 men, most of them Huntington residents (a few were from Islip), “shocked by the bloody Scene” that had occurred just weeks before at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, where patriot Minutemen and British regulars had engaged in a bloody armed struggle, put their signatures on Huntington’s Articles of Association. Only 37 Huntington residents, either Loyalists or those wanting to stay out of the fray, refused to sign. The Articles noted that the signers affirmed their “Love to our Country,” agreed “to whatever Measures may be recommended by the Continental Congress; or resolved upon by our Provincial Convention, for the Purpose of preserving our Constitution, and opposition to the Execution of the several arbitrary, and oppressive Acts of the British Parliament,” and prayed for “a Reconciliation between Great-Britain and America.” The actions of these associators were seen by both patriots and the British as a step towards rebellion. The fact that these men signed these Articles, placing themselves in danger of British retaliation, including imprisonment, seizure of their property, and exile from Long Island, is proof of their patriotic service.

Records show that he enlisted in the Continental Navy as a seaman and became a privateer. Documents and records in the New York Comptroller’s Office that were used in compiling the rolls and rosters for New York in the Revolution (1898), by James A. Roberts, show Richard as among the enlisted men in the naval service. While skirmishing with the British off of Danvers, Massachusetts, he was wounded in the hand. Per several accounts, including the Official Bulletin of the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (March 1909), he was imprisoned by the British on the Caribbean island of Barbados as well as in New York, where he was a prisoner on the Admiral’s ship in New York Harbor. There he witnessed examples of the severity of British naval discipline, including death from lashings. Richard managed to escape to his home in Cold Spring Harbor, but his return was reported to the British, who soon attacked his house, firing through the barred door where Richard stood waiting until the rest of his family were able to find shelter in a neighbor’s home. According to the Huntington historian Robert C. Hughes, Richard’s bravery was recounted in the 1876 speech, “Historic Huntington.” Richard fled through a swamp and the woods to the shore where he was able to board a waiting vessel.

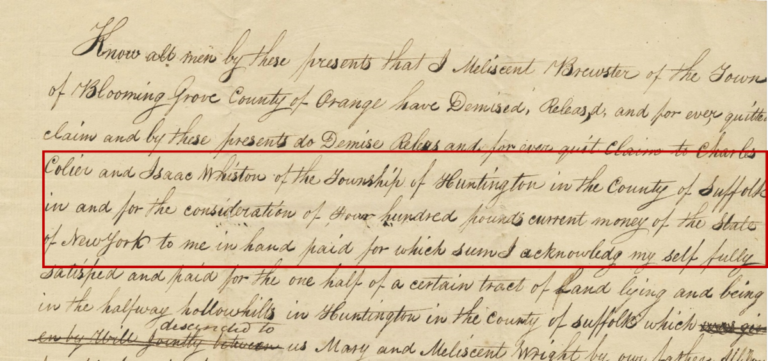

Richard married Mary Bernard about 1779. She was born in 1762. They had several children: Titus Conklin (1788-1818), Rebecca Conklin Rogers (1792-1847), Stephen Bernard Conklin (1794-1812 or 1814), Richard Montgomery Conklin (1799-1877), and Henry Alonzo Conklin, born in 1806. All the children were born in Cold Spring Harbor where the family resided with Richard’s brother Titus. After Richard’s father’s death on July 24, 1787, in Huntington, his mother, Rebecca, remarried the widowed Hubbard Conklin (Conkling) (see) on January 7, 1789. Rebecca died on January 2 or 22, 1793.

During the War of 1812, Richard helped capture a vessel loaded with grain and flour intended for the British. His son, Stephen Bernard Conklin, died at sea as a privateer in either 1812 or 1814. Richard’s brother, Captain Enoch Conklin, died in 1814. Enoch had become a privateer during the war and had his own ship, the Arrow. According to Francis Ferdinand Spies’s 1933 book, New Rochelle, New York, Cemeteries, Enoch and his crew were given a commission by the United States government and sailed from the port of New York in September 1814. Neither vessel, captain, nor any crew members were ever seen again. The Refugees of 1776 from Long Island to Connecticut notes that Stephen Bernard Conklin had been an officer on that ship and was lost at sea.

Richard died on August 11, 1818, in Huntington. Not only is he interred in Huntington’s Old Burying Ground, but his father, mother, and stepfather are also interred there. His original marble gravestone, with an iron repair, displays his name, date of death at age at death, and an epitaph. In 1973, Rufus B. Langhans, Huntington’s Town Historian, applied for a a government-issued marble headstone. That gravestone is inscribed “Seaman, Privateer Service, US Navy, Rev War.” Richard’s widow, Mary, expired on August 6, 1828, and is interred in the Old Burying Ground as well, along with the couple’s daughter, Rebecca Conklin Rogers and her husband, Daniel Rogers.