By Barbara LaMonica

An act banning the importation of slaves to the United States was passed by Congress in 1807. While prohibiting American ships from engaging in the international slave trade and from leaving or entering American ports, the act did not outlaw the slave trade within the United States. Many European countries also banned the slave trade, but there was still a demand for slaves in their overseas colonies, especially in Cuba, which became a major port of call for African slaves. And many slaves were smuggled into the southern states through Texas and Florida before these territories were admitted to the Union in 1845.

It was hoped the law would eventually lead to the abolition of slavery altogether, but enforcement was lax and underfunded. Even though Congress did grant federal monies to create naval anti-slaving patrols, the Confederate states often blocked sufficient funding, while slave traders and ship owners devised several methods for circumventing the ban. In addition, because of U.S. limited ability to enforce the slave trade, many foreign slave vessels utilized the American flag. It was not until the Confederate states left congress in 1861 that it became feasible to provide more funds to police the ports and high seas.

One of the main methods of evasion utilized by slave traders was to disguise slave ships as whaling vessels. Former whaling ships easily lent themselves to be repurposed as slavers. The large hold of a whaling ship could easily accommodate extra lumber which was converted to a slave deck. Try-pots, which were large pots used to render oil from whales became cooking pots to feed the slave cargo. Large supplies of food and water would not arouse suspicions since whaling vessels were often gone for years.

New York City became the slave traders’ base of operations for financing and outfitting vessels. Several downtown firms were actually covers for illegal offices financed by Cuba to send vessels disguised as whalers out of New York to the African coast. It was estimated that within one year over 80 slavers left from New York.

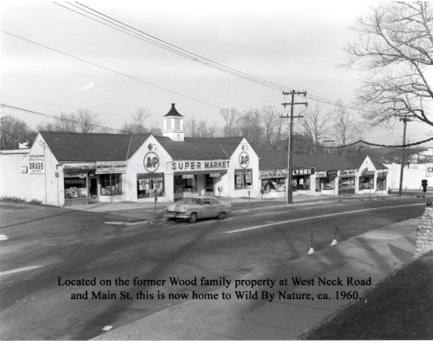

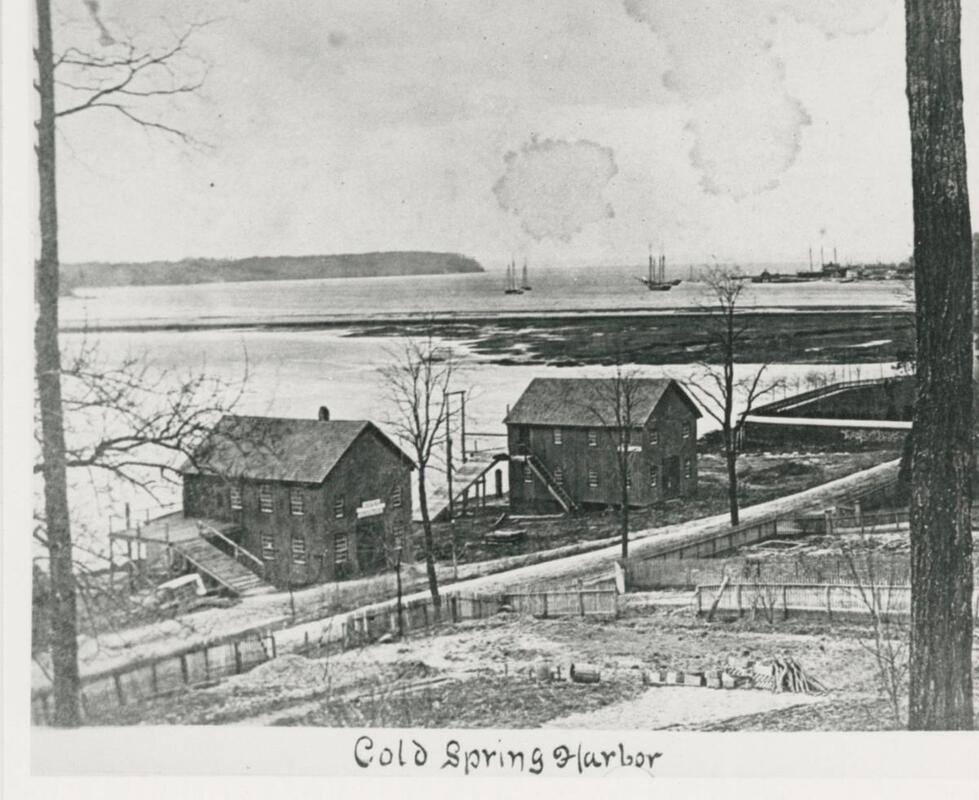

By extension, the smaller harbors of Long Island such as Sag Harbor, Greenport and Cold Spring Harbor provided refuge for slave traders due to the absence of US marshals and lenient port officers. Local historian Frederick P. Schmitt found the records and papers of Jacob C. Hewlett who was Cold Spring Harbor’s customs inspector. Hewlett was somewhat notorious for not noticing “odd supplies” on board such as multiple water casks, extra planks, hatches with gratings, and shackles. Schmitt observed an entry in Hewlett’s records for the ship Romulus which cleared port on October 31, 1860. However, being an expert on Cold Spring Harbor’s whaling industry, he never came across the name Romulus. According to an American vessel database the last voyage she made was May 9, 1860 out of Mystic.

Previously Romulus sailed out of Mystic on whaling voyages. She was later sold to an anonymous buyer in Cold Spring Harbor. She was often observed receiving odd supplies under the cover of night from a tugboat from New York. Custom officer Jacob Hewlett was rumored a “decided old fogy-never without a pipe in his mouth- and that it is no difficult matter for any vessel to get “papers” from him.” (Whaleman’s Shipping List Nov, 1850.)

There were very little abolition sentiments in the maritime industry as the profits from the slave trade were too much of a temptation. According Schmitt whale ships netted an average of $16,000, but a cargo of 600 slaves brought to Cuba or Brazil averaged $250,000 or more.

Eventually British squadrons closed off Cuban ports and by 1864 the trade was all but suppressed.

Works cited: Reilly, Kevin S. Slavers in Disguise: American Whaling and the African Slave Trade, 1845-1862. The American Neptune, Salem, Mass., http://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35556022866412

Schmitt, Frederick P. Satan’s Ships. Undated article found in Andrus & Harriet Valentine Papers, Box 26, Folder 4. Huntington Historical Society Archives.