By Barbara LaMonica

Before the iconic “Rosie the Riveter” there was another corps of women, widely known at the time, but largely forgotten now, who contributed to an American war effort. The Farmerettes, better known as the Women’s Land Army of America, played a vital role in sustaining American agricultural production during WWI while many farmworkers were fighting overseas, or had taken higher paying jobs in defense factories.

The Farmerettes were inspired by the British Land Lassies, a civilian core of women organized to work on farms replacing the men who had been called up to military service. Since in those days farming was not highly mechanized the women provided the extra labor needed to ensure enough harvest to feed the nation.

In June 1917 Ida Ogilvie, a geology professor at Barnard College, established the first Women’s Agricultural Camp in Bedford, New York. This was an experimental facility where over a period of 4 months over 100 young women lived together in a camp where they were trained in farming skills such as driving tractors, plowing, planting, and harvesting as well as physical conditioning. The women were then placed on farms, but the farmers had to agree to certain conditions. The Farmerettes, strongly influenced by the Suffrage movement, demanded that the farmers agree to an 8-hour day, and the women had to be paid the same wages as the men. Very progressive for those times!

The Bedford camp model was duplicated throughout the United States, and eventually more than 20,000 women were recruited from cities and colleges and placed on rural farms in 25 states. On Long Island most Farmerettes were placed on farms out east including Bridgehampton, Riverhead, and Patchogue.

This was not a government program but was established and funded by a group of women’s organizations including garden clubs, women’s colleges, the YWCA, and especially the suffrage societies. Local schools and universities, including Farmingdale Agricultural College on Long Island, provided training. The camps or barracks furnished rooms and board as well as transportation to and from the farms. However, they were unsuccessful in procuring government funding as the Departments of Agriculture and Labor stated that farming should only be performed by men and therefore would not recognize the Women’s Land Army. Of course, this was in spite of the fact that women had owned and worked their own farms for years.

At first it was difficult to convince farmers to hire women. But as the reputation of hard- working women and prolific crops spread, waiting lists had to be created. An amusing headline in the Brooklyn Eagle of August 11, 1919, states “Big Spuds Scare L.I. Farmerettes: Potatoes Growing So Big They May Not Be Able to Lift Them.” According to the article farmers were apprehensive that the women would not be able to lift bushels with potatoes twice the size. But their manager assured farmers that the women were “healthy and husky”, and so it seems, as over $500,000 worth of potatoes were shipped from Riverhead and Southold alone. A New York Times headline of September 8, 1918, states, “New York Farmers Break All Records”. According to the article, thanks to the Farmerettes the apple crop was nearly five times that of the year before, and the spring wheat crop was considered the greatest ever.

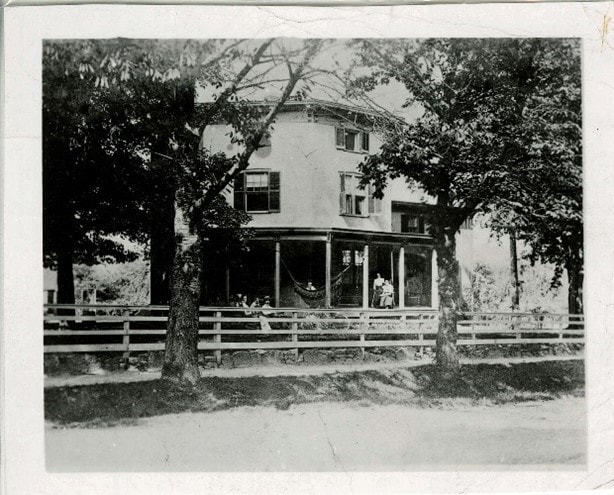

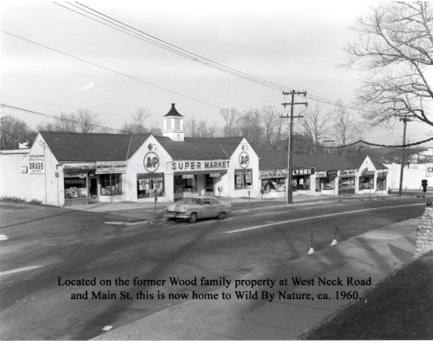

Although most Farmerettes on Long Island worked on large farms on the east end, many of the barracks were throughout the Island including Cold Spring Harbor and Huntington. Women from Brooklyn and Queens were in Cold Spring Harbor. They utilized an historic building on the Jennings estate for administration, and the adjoining casino for sleeping. (Long Islander, August 15, 1919, pg.10). By 6:45 am the first squad of 7-10 women would be transported along with supervisors to a work site, the last squad leaving at 7:45 for farms closer to home base.

Fred Allen, whose oral history was recorded by the Huntington Historical Society in 1987, clearly remembers Farmerettes living in Huntington on Park Avenue, probably near the Marsh estate.

Yeah, on 168 Park Avenue. If you go there, the fence is still there, and the big white house is still there. Let me tell you something else, and in my youth next to that estate were the girls. What they call Farmerettes from Brooklyn. And if you go there, they split the houses. There’s a house here and a house here. Split it in half. It was that big, all girls. And their property ran from New York Ave way back and it used to be a big oak where they used to go out and sing every night. And where we live, you could hear… they called Campfire Farmerettes, oh yeah, but they were Farmerettes, and they farmed the whole place.” (Interview Fred Allen, December 10, 1987)

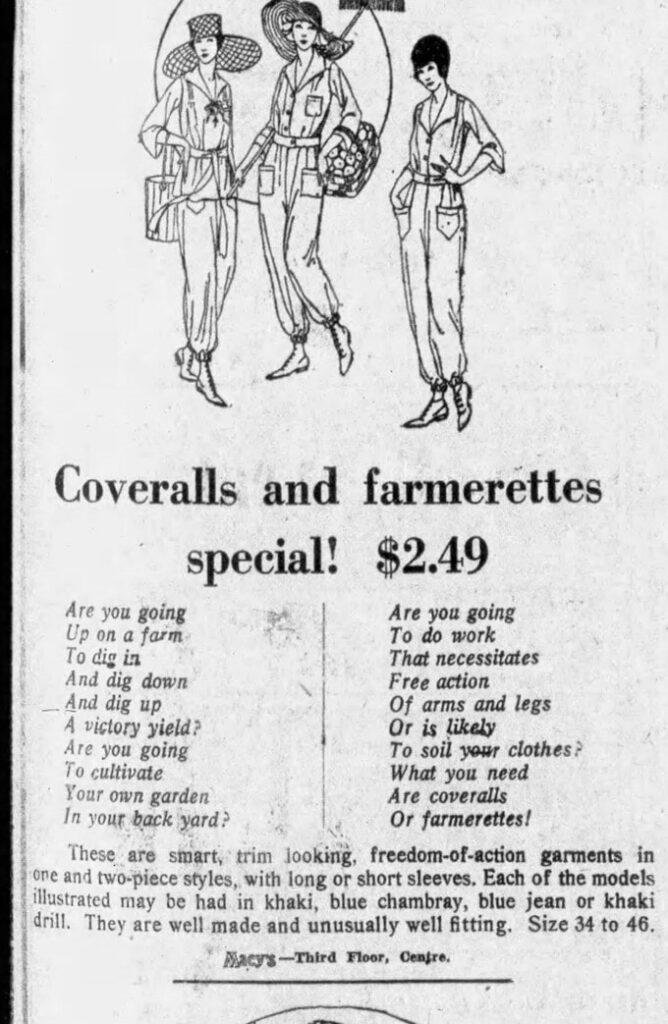

Eventually Farmerettes became so popular, a straw hat and overalls were a badge of honor as well as a fashion statement, as evidenced by the added below.

Due to the success of the Farmerettes, after the war women began to take farming seriously, and society’s attitude changed. Some women were even offered permanent jobs, such as one woman who eventually managed a dairy farm. Colleges started to offer agricultural courses for women, as one woman stated,

“Men work better when they work alongside women. I am sure the farmer for whom I worked never got so much work out of his boys as when the women came to work among them…the men rather than have the women get ahead of them in any respect kept their work up to the mark better than they had before”. (New York Times, April 13, 1919.)

For further reading see: Fruits of Victory the Women’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Elaine Weiss. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, c2008.